| Letters

from Robert Dale Hutchins to his wife, Grace Louise Essex Hutchins He wrote daily letters to his wife back in Des Moines from the military front lines. These are shared by his family to illustrate some specifics of field front activity. |

|

| November

17, 1944 No location given. My Dear Grace: This is the second letter today. I hate to sit around doing nothing. The black jack game has broken up, and I feel like writing to you. So here goes. I haven’t the faintest idea what I shall write about, but I guess I can think of something. Let me see, now. I never did tell you about the odd voodoo rites that are practiced down here, deep in the woods and swamps. Or how Fred and I stumbled onto one of those meetings one evening when we were out looking for hickory nuts. There is an old abandoned cemetery about two or three miles south of camp. The first time I saw it was once when our outfit was on a hike. We had been given a rest and we were just sitting around resting. From where I was sitting, I could see a rounded, grayish white object through the underbrush. Wondering what it was, I walked over to see, and there before me, was an old abandoned cemetery. It was ancient. The headstones were made of rounded slabs of wood that had once been painted white. Some of them had fallen down and were slowly rotting away. Some stood at angles, not yet ready to fall over, and some graves had nothing on them. The woods had almost taken the place over, and the vegetation was quite thick, except for one area which was a roughly circular spot and almost bare. There were three old graves in that area and I could hardly make them out, they were so nearly level with the surrounding ground. All in all, there were about seventy or eighty graves there. I didn’t count them, or even go into the place. I just stood at the old wooden gate, with it’s huge old fashioned rusty padlock, tightly locked by rust and key both. The gate was all that was left of the wooden fence which had once surrounded the burying ground. I was standing there, as I said, looking at the gloomy, unkempt place, when I heard the whistle blow. As I turned to go back to the company, I caught a furtive movement; in the underbrush to my left, out of the corner of my eye. I looked straight at the brush, and walked over to it, but could find nothing there. I figured I had imagined seeing a movement there, so I rejoined the outfit, and we continued our hike, eventually ending up back here at camp. A few days after our hike, Fred suggested we go after some hickory nuts. I was the only one in the bunch who would go, so we hunted around for a sack, and finally found an old onion sack at the mess hall. After retreat, we set out for the woods, and before dusk, we had a bag full of fine hickory nuts. As we put the last handful into the bag and tied it, the gloom was getting pretty thick, and it was possible to see for only a few yards through the trees. There are lots of different trails through the woods, the stars were coming out although there was no moon, and we knew we were south of camp. We could guide on the North Star and hit camp right on the nose, so we struck out. We soon came upon a trail that ran fairly well in a northerly direction, so we stayed on it. We crossed an old decayed footbridge, over a slow moving, black, scum covered, trickle of water, and finally the trail petered out. As we finally decided we had no trail to follow, we saw a faint light glimmering through the trees, ahead of us. It was quite dark by now, so we kept on toward the light, stumbling through the undergrowth, and making enough noise for an army. We figured it was some outfit out on bivouac, and that the light we saw was a small fire. Perhaps we shouldn’t have made so much noise, but we were only about two or three miles from camp and were in a hurry to get back. As we got within about a hundred feet of the fire, I suddenly realized where we were. We were approaching the old cemetery, and the fire was inside the graveyard, among the graves. I cautioned Fred, and we stole up very quietly. We came to the gate and it was standing wide open, the open padlock dangling from a nail on the fence post. I wondered, even at that moment, why the gate had been opened when all anyone had to do, was walk around it. I still wonder why, and I guess I’ll never be able to figure that one out. Now, we could see the fire very plainly, and the people sitting around it. They were talking quietly among themselves, some negroes, and some that looked white from the distance we were viewing them. Fred and I whispered together and decided to hang around and see what was going on. Perhaps five or ten minutes later, one ugly old negress got up, reached in her pocket, and threw something into the fire, and it flared briefly and threw off a dense cloud of smoke. Oily, black smoke, which seemed reluctant to rise into the air. It hung perhaps ten or fifteen feet in the air and drifted slowly to one side. As the fire subsided, a chant began, and it was accompanied by the beat of a tom-tom or drum. Slowly the beat of the drum increased in tempo and the chanting grew wilder. We couldn’t make out the words, but it didn’t sound so hot. Full of minors and lots of wailings. The old Negress went off to one side and returned a minute later, leading a white goat, and she stood holding it by a very short rope, in the center of the circle, beside the fire. The music [if it could be called music.] rose to a climax and stopped very suddenly. As the music stopped, the old negress cut the goat’s throat with a long knife. I never did see where she got the knife and I was watching her all the time. The tom-tom began to beat, the chant started again, and she bent over the dead goat. As she stood up again, I could see she held something bloody in her hand. Fred whispered that it was the goat’s heart she held in her hand, and suggested that we leave. I agreed, but then we decided to see a little more. By now she was cutting the heart into small pieces, and passing them around the circle. The chant stopped again and they all sat down cross legged, and proceeded to eat the pieces of meat. This time we definitely decided to take off, and we did so. We made the rest of the trip to camp with no difficulty, and that’s the last time we went after hickory nuts in that direction. Well, must close, as lights out. Love, Bob |

|

| March

21, 1945 France My Dear: Jackpot! Seventeen letters from you, one from Ellen, one from Dad, Dutchie, John Henry Jr. and one from the U.S. Rubber Co, asking my present address. I’m answering your letters first of course. The rest can wait if necessary. I’ll take the three V mail first. The main theme in most of your letters is the kids. And you wonder why I don’t mention them more often so I’ll try to explain to your satisfaction. First, I think of the kids and you constantly and I have assumed that you knew it. Evidently I was wrong in that assumption but I assure you it is so. I can’t help but compare the kids with the French and Belgium kids of the same age and the difference of their lots. The same with you and our folks. When I see a kid standing around looking big eyed at the Americans Soldiers envying them every piece of candy or stick of chewing gum until finally they ask for some. I think of Bobbie, Dutchie and Jimmie. Even the ones that can barely toddle along, know enough English to say “chocolate, chewing gum, and cigarette.” I can’t see you taking the soldiers laundry to them in a basket or barracks bag so large that you stagger under the load and I could never hear you asking “You have a cigarette for me?” An English soldier told me his wife and two children receive 15 shillings a month from his government. Just about $3.00 in good old American money. And when I see the older men and women, competing with the agile youngsters of 12 or 13, and trying to get the soldiers to empty the garbage in the mess kits into their own buckets. I Think of how awful it would be were your mother or father, or mine, in such a position. Of course a position has it’s points. Perhaps a soldier will leave a whole piece of bread, or a large piece of meat uneaten. That, my dear, is magnifique. Such a piece of bread or meat can be placed in a pocket for future use, and if one is diligent and courteous to the soldiers, one might perhaps fill a pocket completely with good things to eat. And the kids standing around watching us eat. It ruins my appetite. Last Sunday we had fried chicken for dinner and I gave all of it to some kid, even the coffee. They don’t beg our meals from us or any thing like that. As a matter of fact, they wait until we are entirely through and then ask if they can have the rest of the coffee, or cocoa and they drink it to the very dregs. Not a drop is left. I hate to think of Bobbie or Dutchie doing that but it always brings them to mind. So you see everything I see, everywhere I go and everyone I meet, brings all of you to mind, especially the kids. I may not ask you a lot of questions about them but I consider that unnecessary as you tell me in detail, in every letter all about them, especially Jimmie and Billie. There was more to this letter but it was personal to his wife so I (his daughter, Mary) left it off. |

|

|

|

|

|

| May

4, 1945 Belgium My Dear: A man stood with his back against a stone wall. On either side of him, others were lined up against the wall. Among them, his two brothers, and his son. They weren’t tied or bound in any manners, further resistance was futile. They simply stood with their backs against the cold grey stone and perhaps some leaned against it for support. A machine chattered briefly in short bursts and the man, his brothers, his son, and his comrades lay in crumpled heaps at the foot of the wall. The S.S. troops had once again meted out German justice. An old lady, a grandmother had 30 Belgium soldiers hidden in her home for three successive nights. Little groups of the soldiers melted away into the darkness, making a dash for freedom. The next morning, early, the S.S. troops surrounded the house and within a few minutes their work was done. They marched away by themselves. American tanks were taking a town and the snipers were busy. Suddenly the turret on a tank opened, a soldier’s head and shoulders showed briefly as he threw a grenade into a window. Four seconds later, a mother and her little crippled girl were dead inside the room. The letter telling of these events in the life of one family was received at Joseph’s house. The family was that of his wife and altogether, eleven are dead. He and his wife so say “Cest la guesse”, as though it were a most natural thing. She has only Joseph, Monique and her mother left, yet she apologized profusely for crying in front of me. I felt very out of place and left as soon as I could. Joseph would take nothing for the ring he made for me, so I gave him a package of tobacco, a candy bar and a package of gum. Something for all of them and they will like it better than any money I would have paid. I don’t know why I bother telling you of this except that it’s a fairly typical story of these people. Others worse perhaps, and others not so bad. Many people are returning to their homes now and we haul lots of them in box cars and gondolas. The other day one of these repatriots returned to this town. He had been gone for five years. Arriving at his house, he knocked on the door. His daughter answered and recognized him at once. She hugged and kissed him until finally he asked were mama was. “She went to the store to buy milk for baby brother.” was the answer. “Baby brother!” “Baby brother!” The man entered the house and ran upstairs. There lay a tiny baby on the bed and it’s neck was snapped in a instant. The man went downstairs again and as the door opened to admit his wife, the little girl ran to her screaming “Baby brother!” The startled woman dashed upstairs. There lay the dead baby. An instant later, her husband was beating her face with his fists. She was nearly dead before the police arrived and took the man in custody. And the whole thing was an error. The baby dead, the woman nearly so, the sights the daughter witnessed. The baby was a refugee from Liege where the buzz bombs had been hitting and the mother and little girl had fondly called him “Baby brother”. Some mistake, huh? Well I had better get to your letters of the 23rd and 26th. The first letter doesn’t call for any answer and it’s short and hurried as though you write merely from a sense of duty. The next runs in the same vein, although somewhat better. Really nothing to answer in either of them. What’s up? The letter I’ve just written is a dismal sort of affair. But really it’s the first time I’ve felt like writing for some time. When I started, I was so sleepy I was yawning constantly, and now I can hardly keep my eyes open. Still, I feel like writing more of this junk and I would only I’m afraid you wouldn’t like it. I guess Joseph’s wife, apologizing for crying because her best comrade, her father, is dead is really what got my goat. I saw a parade a few days ago. Sort of a communist parade I guess. Lots of flags, lots of Russian flags but no American flags. Lots of houses fly the hammer and sickle on the slightest occasion. I’m just putting down whatever pops into my so called mind as you can easily see. We see sights and little happenings and we hear stories and pay little attention to any of them. At the time I see or hear these things I think perhaps I’ll tell you of them. Then I can’t think of anything to write at all. Your letters are few and far between but I enjoy them when I do eventually get hold of them, so keep it up Honey. I guess I’ll sign off now as it is very late. The other fellows have been in bed for quite some time. Perhaps my next letter will be better. I hope so but I’ve given up promising that they will. Love to you all and you especially, Bob |

|

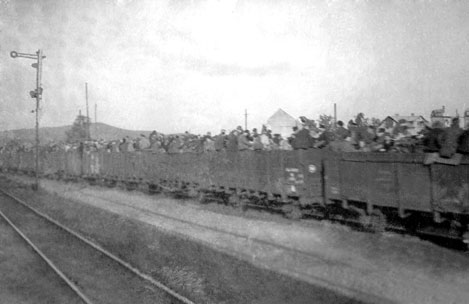

| May

13, 1945 Holland Honey: I must apologize to you again and again. I have written very few letters lately and I know I should write oftener. My only excuse is the fact that we have been so very busy. I wrote last on the ninth and am enclosing that letter with this one. There have been several trips between these letters and many trains. As many as four trains a trip, although that’s a little unusual, there’s usually only one or two trains a trip. Today we dead headed from Liege to Maastricht (The Netherlands) and we are waiting for a train now. We came upon a train of liberated Hollanders and I think I told you how they are all over a train. On top of the cars, between the cars, on the sides, etc. Today the thing I’ve been expecting happened. We passed another train and the doors [Swinging doors.] on a gondola were open. It swiped the side of our train from one end to the other. Some had their legs badly cut and some had their legs cut off. We pulled the air and dropped off as soon as we realized what was happening but it was all over by the time our caboose had passed the car that was doing the damage. Three of the liberated had been pulled out of their car and were lying between the tracks. One was dead by the time we got there and the other two, I think, will die. The doctor finally arrived on his bicycle and did what he could but we had already put tourniquets on, and the Red Cross [Belgium] had taken care of the ones in the cars. Altogether, three dead and 25 hurt. The mess was finally cleaned up and the ones not seriously injured were kept on the train. As we pulled out, others were sitting in the doors. Their legs dangling in spite of our warnings and what had happened to their comrades. One fellow, both legs gone, was within fifteen miles of home after being a prisoner for five years. His wife was with him. But I think she came on with the train. I made some of her friends take her away twice and didn’t see her again when he was carried away so I guess they kept her in the car. Such accidents are so unnecessary but they don’t realize the dangers of a railroad and are so happy to be getting home, they are apt to do anything. Yesterday, 20 out of 30 on top of a train had their heads cut off by a wire. They were French soldiers. Enough of this talk. I don’t want this letter to be revolting. The incident is so fresh though, that I write of it. There’s nothing new here, except beaucoup work. Lots of rumors that we will move again soon and most of the rumors say Germany. The next favorite rumor is the CBI. That reminds me that I owe Mom a letter and I can’t write it tonight, so please tell her hello and I’ll try to write the next time I write to you. With good luck, that will be tomorrow. I owe John Henry and Don Robb a letter too and have for over a week. Perhaps I’ll answer them inside of another week, perhaps not. No letters from anyone else. One good thing about working like this is that if I get no mail [From anyone but you.] I don’t feel as if I owe them a letter. I should write you every day. Letters or no letters. [Mostly no letters.] Another train of liberated just pulled out singing. They are in open cars and they are cold but happy. I can hear an accordion and singing from another train. Whole families, babies and all that the entire group can carry. Any group of people that would cause such discomfort, suffering and death should be wiped out entirely. I am deeply grateful that the war has touched us in such a small way. I would stay here from now on if that would keep you, the kids and our folks from anything such as I see daily. Of course that isn’t necessary but I would do it and be glad of the chance. I could write lots more, Honey but I’ve just got to get some sleep now. When the fireman plays out, I relieve him and the same for the engineer. When we first started, we worked as much as 60 and more hours but now our longest is 22 [Over last one.] and usually not near that much. I’ll try to write tomorrow, I mean today as it is after Midnight. So until then, Sugar. Love, Bob |

|

| Home

|

Back/allyears | WWI | WWII

| Korea | Vietnam

| Afghanistan/Iraq | Hutchins

page ©2025-csheddgraphics All rights reserved. All images and content are © copyright of their respective copyright owners. |

|