USS

Roosevelt (DDG-80)

Checking out this entry.

McDonnell Douglas A-4E Skyhawk

The Douglas A-4 Skyhawk is a carrier-capable attack aircraft developed

for the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps. The delta

winged, single-engined Skyhawk was designed and produced by Douglas

Aircraft Company, and later by McDonnell Douglas. It was originally

designated the A4D under the U.S. Navy's pre-1962 designation system.

The Skyhawk is a light-weight aircraft with a

maximum takeoff weight of 24,500 pounds (11,100 kg) and has a top speed

of more than 600 miles per hour (970 km/h). The aircraft's five hardpoints

support a variety of missiles, bombs and other munitions and was capable

of delivering nuclear weapons using a low altitude bombing system and

a "loft" delivery technique. The A-4 was originally powered

by the Wright J65 turbojet engine; from the A-4E onwards, the Pratt

& Whitney J52 was used.

Skyhawks played key roles in the Vietnam War, the Yom

Kippur War, and the Falklands War. Fifty years after the aircraft's

first flight, some of the nearly 3,000 produced remain in service with

several air arms around the world.

Attack Squadron VA-46 or ATKRON 46

Attack Squadron 46 (VA-46 or ATKRON 46) was an attack squadron of

the United States Navy that was active during the Cold War. VA-46 was

deactivated as part of the post-Cold War drawdown of forces on 30 June

1991.

On 25 July 1967 the Clansmen took part in their first

combat operations during the Vietnam War flying from the USS Forrestal

in Yankee Station. A few days later on July 29, while aircraft were

being prepared for the second launch of the day against targets in North

Vietnam, a fire broke out on the flight deck of the Forrestal. Flames

engulfed the fantail and spread below decks, touching off bombs and

ammunition. Heroic efforts by VA-46 personnel, along with other members

of Carrier Air Wing 17 and ship's company, brought the fires under control.

Damage to the carrier and aircraft was severe, and the casualty count

included 134 dead and 62 injured. The squadron lost seven A-4E Skyhawks

during the fire.

USS Forrestal (CVA-59)

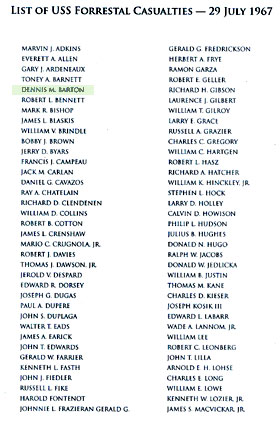

The 1967 USS Forrestal fire was a devastating fire and series of chain-reaction

explosions on 29 July 1967 that killed 134 sailors and injured 161 on

the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal (CVA-59), after an electrical anomaly

discharged a Zuni rocket on the flight deck. Forrestal was engaged in

combat operations in the Gulf of Tonkin during the Vietnam War at the

time, and the damage exceeded US$72 million (equivalent to $509 million

today) not including damage to aircraft. Future United States Senator

John McCain was among the survivors.

Forrestal had departed Norfolk, Virginia in early June 1967. Upon completion

of the required inspections for the upcoming WESTPAC Cruise, she then

went on to Brazil for a show of force. She then set sail around the

horn of Africa, and went on to dock for a short while at Leyte Pier

at N.A.S. Cubi Point in the Philippine Islands before sailing to "Yankee

Station" in the Gulf of Tonkin on 25 July. For four days in the

gulf, aircraft of Attack Carrier Air Wing 17 flew about 150 missions

against targets in North Vietnam.

By 1967, the ongoing naval bombing campaign from Yankee

Station represented by far the most intense and sustained air attack

operation in the navy's history, with monthly demand for general purpose

bombs ("iron bombs") greatly exceeding new production. The

on-hand supply of bombs had dwindled throughout 1966 and become critically

low by 1967, particularly the new 1000-lb. Mark 83, which the navy

greatly favored for its power-to-size ratio: a carrier-launched A4

Skyhawk, the navy's standard ground attack aircraft of the period,

could carry either a single 2000-lb. bomb, or two 1000-lb. bombs,

with the ability to strike two separate hardened targets in a single

sortie being seen as more desirable in most circumstances. Until 1971,

the US Air Force's primary ground attack aircraft in Vietnam was the

much heavier land-based F-105 Thunderchief which could carry 2 2,000-lb.

M118 bombs and 4 750-lb. M117 bombs (both of which had large stockpiles

available) simultaneously on a single sortie, and thus did not need

to rely as heavily on the limited supply of 1000-lb. bombs the way

the navy did.

In training, the damage control team specializing in

on-deck firefighting for Forrestal (Damage Control Team #8, led by

Chief Petty Officer Gerald Farrier) had been shown films of navy ordnance

tests demonstrating how a 1000-lb bomb could be directly exposed to

a jet fuel fire for full 10 minutes and still be extinguished and

cooled without an explosive cook off. However, these tests were conducted

using the new Mark 83 1000 lb bombs which featured relatively stable

Composition H6 explosive filler and thicker, heat-resistant cases

compared to their predecessors; H6, which is still used in many types

of naval ordnance due to its relative insensitivity to heat, shock

and electricity, is also designed to deflagrate instead of detonate

when it reaches its ignition point in a fire, either melting the case

and producing no explosion at all or at most a subsonic low order

detonation at a fraction of its normal power.

The day before the accident (28 July), the Forrestal

was resupplied with ordnance from the ammunition ship USS Diamond

Head. The load included 16 1000-lb. AN-M65A1 "fat boy" bombs

(so nicknamed because of their short, rotund shape), which the Diamond

Head had picked up from the Subic Bay Naval Base and were intended

for the next day's second bombing sortie. The batch of AN-M65A1 "fat

boys" the Forrestal received were surplus from World War II,

having spent roughly three decades exposed to the heat and humidity

of the Philippine jungles while improperly stored in open-air Quonset

huts at a disused ammunition dump on the periphery of Subic Bay Naval

Base. Unlike the thick-cased Mark 83 bombs filled with Composition

H6, the AN-M65A1 bombs were thin-skinned and filled with Composition

B, an older explosive with greater shock and heat sensitivity; Composition

B also had the dangerous tendency to become more powerful (up to 50%

by weight) and more sensitive if it was old or improperly stored.

The Forrestal's ordnance handlers had never even seen an AN-M65A1

before, and to their shock the bombs delivered from the Diamond Head

were in terrible condition; coated with "decades of accumulated

rust and grime" and still in their original packing crates (now

moldy and rotten), some were stamped with production dates as early

as 1935. Most worryingly of all, several bombs were seen to be leaking

liquid paraffin phlegmatizing agent from their seams, an unmistakably

dangerous sign the bomb's explosive filler had degenerated with excessive

age and exposure to heat and moisture.

According to A-4 Skyhawk pilot Lieutenant Rocky Pratt,

the concern and objection induced in the Forrestal's ordnance handlers

was striking, with many afraid to even handle the bombs; one officer

wondered out loud if they would even survive the shock of a catapult

assisted launch without spontaneously detonating, and others suggested

they immediately jettison them into the sea. Since no one wanted to

be responsible for scrubbing the next day's missions, the decision

was made by the Forrestal's ordnance officers to report the situation

up the chain of command to Captain John Beling and inform him the

bombs were, in their assessment, an imminent danger to the ship and

should not be kept on board.

Faced with this, but still needing 1000-lb. bombs for

the next day's missions, Beling demanded the Diamond Head take the

AN-M65A1s back in exchange for new Mark 83s, but was told by the Diamond

Head that they had none available to give him. The AN-M65A1 bombs

had been returned to service specifically because there were not enough

Mark 83s to go around. According to one crew-member on the Diamond

Head, when they had arrived at Subic Bay to pick up their load of

ordnance for the carriers, the base personnel who had prepared the

AN-M65A1 bombs for transfer assumed the Diamond Head had been ordered

to dump them at sea on the way back to Yankee Station; when notified

that the bombs were actually destined for active service in the carrier

fleet, the commanding officer of the naval ordnance detachment at

Subic Bay was so shocked he initially refused the transfer, believing

a paperwork mistake must have been made. At risk of delaying the Diamond

Head's departure, he refused to sign the transfer forms until receiving

written orders from CINCPAC on the teletype explicitly absolving his

detachment of responsibility for their terrible condition.

With orders to conduct strike missions over North Vietnam

the next day and no replacement bombs available, Captain Beling reluctantly

concluded he had no choice but to accept the AN-M65A1 bombs in their

current condition. In one concession to the demands of the ordnance

handlers, Beling did agree to store all 16 bombs alone on deck in

the "bomb farm" area between the starboard rail and the

carrier's island until they were loaded for the next day's missions;

standard procedure would have been to store them in the ship's magazine

with the other bombs (where an accidental detonation could easily

destroy the entire ship).

Fire[edit]At about 10:50 (local time) on 29 July, while

preparations for the second strike of the day were being made, an

unguided 5.0 in (127.0 mm) Mk-32 "Zuni" rocket, one of four

contained in a LAU-10 underwing rocket pod mounted on an F-4B Phantom

II, accidentally fired due to an electrical power surge during the

switch from external power to internal power. The surge originated

from the fact that high winds had blown free the safety pin, which

would have prevented the fail surge, as well as a decision to plug

in the "pigtail" system early to increase the number of

takeoffs from the carrier (see below).

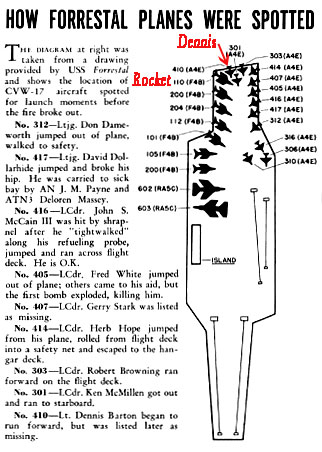

A drawing of the stern of Forrestal showing the spotting

of aircraft at the time (below). Likely source of the Zuni was F-4

No. 110. White's and McCain's aircraft (A-4s No. 405 and 416, respectively)

are in the right hand circle.The rocket flew across the flight deck,

striking a wing-mounted external fuel tank on an A-4E Skyhawk awaiting

launch, aircraft No. 405, piloted by Lieutenant Commander Fred D.

White.The Zuni Rocket's warhead safety mechanism prevented it from

detonating, but the impact tore the tank off the wing and ignited

the resulting spray of escaping JP-5 fuel, causing an instantaneous

conflagration. Within seconds, other external fuel tanks on White's

aircraft overheated and ruptured, releasing more jet fuel to feed

the flames, which began spreading along the flight deck.

The impact of the Zuni had also dislodged two of the

1000-lb AN-M65 bombs, which fell to the deck and lay in the pool of

burning fuel between White and McCain's aircraft. Damage Control Team

#8 swung into action immediately, and Chief Gerald Farrier, recognizing

the risk and without benefit of protective clothing, immediately smothered

the bombs with a PKP fire extinguisher in an effort to knock down

the fuel fire long enough to allow the pilots to escape. The pilots,

still strapped into their aircraft, were immediately aware that a

disaster was unfolding, but only some were able to escape in time.

Lieutenant Commander John McCain, pilot of A-4 Skyhawk side No. 416

next to White's was among the first to notice the flames and escaped

by scrambling down the nose of his A-4 and jumping off the refueling

probe shortly before the explosions began.

Damage Control Team #8 had been assured of a 10 minute

window in which to extinguish the fire and prevent the bombs from

detonating, but the Composition B bombs proved to be just as unstable

as the ordnance crews had initially feared; after only slightly more

than 1 minute, despite Chief Farrier's constant efforts to cool the

bombs, the casing of one suddenly split open and began to glow cherry

red. The chief, recognizing a lethal cook-off was imminent, shouted

for his team to withdraw, but the bomb detonated seconds later –

a mere one minute and 36 seconds after the start of the fire.

The detonation destroyed White and McCain's aircraft

(along with their remaining fuel and armament), blew a crater in the

armored flight deck, and sprayed the deck and crew with bomb fragments

and burning fuel. Damage Control Team #8 took the brunt of the initial

blast; Chief Farrier and all but three of his men were killed instantly;

the survivors were critically injured. Lieutenant Commander White

had managed to escape his burning aircraft but was unable to get far

enough away in time; White was killed along with the firefighters

in the first bomb explosion. In the tightly packed formation on the

deck, the two nearest A-4s to White and McCain's (both fully fueled

and bomb-laden) were heavily damaged and began to burn, causing the

fire to spread and more bombs to quickly cook off.

Lieutenant Commander Herbert A. Hope of VA-46 (and

operations officer of CVW-17) was far enough away to survive the first

explosion, and managed to escape by jumping out of the cockpit of

his Skyhawk and rolling off the flight deck and into the starboard

man-overboard net. Making his way down below to the hangar deck, he

took command of a firefighting team. "The port quarter of the

flight deck where I was", he recalled, "is no longer there."

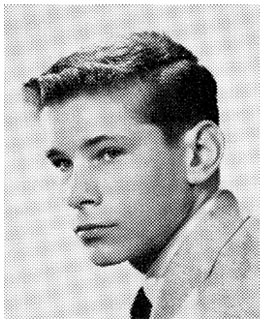

Two other pilots (Lieutenant Dennis M. Barton and Lieutenant

Commander Gerry L. Stark) were also killed by explosions during this

period, while the rest were able to escape their aircraft and get

below.

Nine bomb explosions eventually occurred on the flight

deck, eight caused by the AN-M56 Composition B bombs cooking off under

the heat of the fuel fires and the ninth occurring as a sympathetic

detonation between an AN-M56 and a newer 500 lb M117 H6 bomb that

it was lying next to on the deck. The other Composition H6-based bombs

performed as designed and either burned on the deck or were jettisoned,

but did not detonate under the heat of the fires.

The explosions (several of which were estimated to

up to 50% more powerful than a standard 1000 lb bomb due to the unintentionally-enhanced

power of the badly degraded Composition B) tore large holes in the

armored flight deck, causing flaming jet fuel to drain into the interior

of the ship, including the living quarters directly underneath the

flight deck, and the below-decks aircraft hangar.

Sailors and marines controlled the flight deck fires

by 1215, and continued to clear smoke and to cool hot steel on the

02 and 03 levels until all fires were under control by 1342. The fire

was not declared defeated until 0400 the next morning, due to additional

flare-ups.

Throughout the day the ship’s medical staff worked

in dangerous conditions to assist their comrades. HM2 Paul Streetman,

one of 38 corpsmen assigned to the carrier, spent over 11 hours on

the mangled flight deck tending to his shipmates. The large number

of casualties quickly overwhelmed the ship’s sick bay staff,

and the Forrestal was escorted by USS Henry W. Tucker to rendezvous

with hospital ship USS Repose at 2054, allowing the crew to begin

transferring the dead and wounded at 2253.

Links regarding USS Forrestal (CVA-59) fire:

http://mrhugs2.tripod.com/forrestal.htm

http://mrhugs2.tripod.com/index.html

utube video of incident (poor quality): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=chuiyXQKw3I

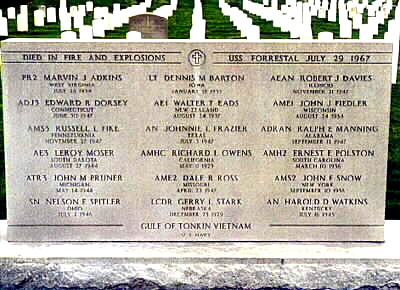

Note: At Denny's memorial held in Des Moines, his widow

told Dick Riley that Denny had been able to evacuate his pilot's position,

but his navigator could not free himself because his cockpit's hood

was jammed. Denny went to rescue his navigator. They both perished.

Note from USS Forrestal historian: Denny did successfully exit aircraft

#410, an A-4E Skyhawk. He was seen running away from his aircraft

heading forward on the flight deck when the first 1,000 lb. bomb exploded,

killing Denny. The A-4E Skyhawk did not have a navigator, so perhaps

Denny was attempting to rescue a navigator from another aircraft.

Other aircraft models on the flight deck included the F-4B Phantom

which accommodated a navigator.

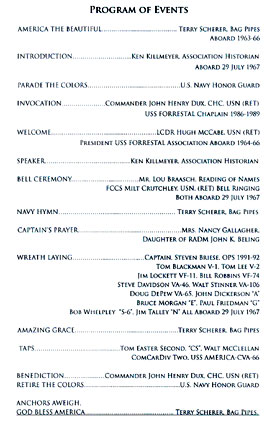

Receiving memorial programs from the 2002,2007,2012 ceremonies held

at the Vietnam Memorial Wall. Those programs will be incorporated

into Denny's page upon receipt.

|